Die Golden Harvest heute in französisch Guayana

“I’ve never been to Africa but it comes up in my dreams …”

The story of the book

I had never actually been to Africa when I first met Raphael Schell at an alternative exhibition over ten years ago. He had chosen to portray his experiences, from memory, on pieces of canvas he had tacked onto large building slabs. There was something mysterious about those pictures. They were entirely devoid of people, like the scene of a crime where the murderer has deposed of the bodies to cover his tracks. The pictures needed explaining, or rather they needed illustrating, even though they weren’t lacking in colour. Then Raphael began telling his story.

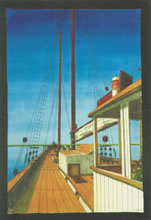

More than twenty years earlier he had been a member of a non-violent group intent on openly importing banned books into Namibia by sailing ship. Their aim was to denounce repression in South Africa, as embodied by censorship and Apartheid, and eventually to bring about the fall of the country’s Apartheid regime. Raphael still keeps a belaying pin, a souvenir of his beloved ship, the SS Golden Harvest. And he still holds nightwatch.

At my request, Raphael recorded his memories onto 40 tapes, an exercise which brought him close to a state of nervous exhaustion but never threatened to free him of his past. He may now be living in Kassel, in central Germany, but to all intents and purpose, he has never left Africa. Unsure of how to go about things, I decided to buy the tapes. We kept it very business-like. But it didn’t help.

For a long time, I felt I couldn’t use the material for my book because Raphael didn’t yet got over Lagos and San Antonio. It had been too much for one lifetime. He had been very young, not even eighteen, and brimming with energy, passion and love. Although he comes from a town far from the coast, he loves the sea, as we all do one way or the other. But with him it was something special.

I’ve met another of the survivors – Hans. He lives in Berlin. He used to be a familiar figure at the big train station, Bahnhof Zoo, where he was a newspaper salesman for the “taz” at night. Hans doesn’t talk as much as Raphael, nor as willingly. He couldn’t go back to his old life in Germany just like that, not after everything that had happened over there. He did manage to safe a box though, full of letters, newspaper articles and transcripts.

The content of the box are a record of the seventies, which was my era. I was the same age as the heroes then. I remember well the political thought and dreams of the time. We didn’t have the german word “Gutmenschen” (good people – patronising term, used to discredit the peace movement) yet. Instead our talk was of “relevant” and “post-capitalism”. For me, Hans’ files didn’t just catalogue Raphael’s story, they were “talkin’ ‘bout my generation”.

I love books, of course. I was all for the Namibian project and would very willingly have taken part myself. What a wonderfully poetic idea – young people from all over the world on board a sailing ship bound for Namibia with a cargo of nothing but books. It sounds like a peacefull idea, but the books – literary donations from universities and bookshops – were pure dynamite

If the South African authorities laying claim to the port at Walvis Bay allowed the books to enter the country their repressive system of surveillance and cencorship would come crashing down about their ears, like a dam which has sprung a leak. If they refused the ship entry, which they could hardly do, given that the crew had gained permission from the UN to dock, South Africa would be exposed to ridicule in the eyes of the international community.

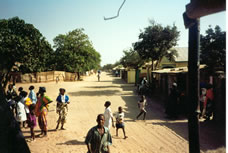

But reading books isn’t enough, especially when they are adventure stories telling tales of the real world. Everyone wants to have their go in their own adventures. I was no different. My first stop was The Gambia. I knew straight away I would have to go back. There was the intensity I had heard on Raphael’s tapes. It was too hot, everything took too long to happen. People were too familiar – I couldn’t help loving them, but I was afraid of them as well.

I was late getting into Lagos, against the express wishes of my wife and in spite of a succinct warning in the Lonely Planet travel guide: “Don’t arrive at night!” Of course, I had prepared myself for what was to come and didn’t admit to be an author, but I hadn’t expected to be interrogated like a criminal. The only reason they didn’t rifle through my luggage was because I didn’t have any (it was lost).

One official yelled at me (apparently the usual tone of address): “I give you one advice: go back now!” Then he said it again, only even louder, as if he thought I was a bit slow: “I told you to go back now!” maybe he was right about me being slow – I didn’t get it. There were signs up on the walls which stated that visitors should avoid giving a tip (I had stuffed dollars into my socks for this very reason) and that defaulters would be arrested.

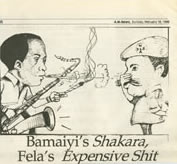

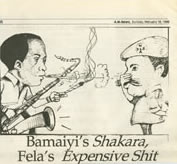

What was I going to do? To cut a long story short, I spend my first night in Nigeria curled up on the couch at the drugs enforcement agency, denied entry into the country, so they said, for my own personal safety. By the next morning, I had made new friends who assured me that Jesus loved me. The news was: Fela Anikulapo Kuti had just been released from prison. He had made the headlines again, just as he had done when the “black ship” docked in Apapa.

I searched out his shop, where I bought a copy of his book “Why Blackmen Carry Shit”. People were not allowed to sit down and listen to Fela’s music for more than ten minutes. It was prohibited to play it in public. Political discussions were likewise illegal. No-one could get near Fela’s “shrine” – in the wake of his release the whole compound was surrounded by police. Fela has since died of AIDS, at least that’s what they say.

In Cape Town, in the land of old enemy, they have at last achieved their goal. They now have a wonderful library, just as the crew of the Golden Harvest might have imagened it. The library is full of books documenting the true history of South Africa, true African thinking and black heritage, books which will help the new Africa define its own identity, just as Fela Kuti demanded, and before him Dr. Kwame Nkrumah.

I headed for an Internet café and straight away started a search for the two peace ships, the SS Golden Harvest and the SS Fri. The latter had also seen action around Mururoa, and in the thirties had helped to ship fleeting Jews out of Germany. They had been, after all, pioneers in the fight for such a freedom library. I then took refuge at the home of Jans Rautenbach, a filmmaker, whose work includes a documentary film on the history of Africa.

The internet search was a dead loss. No wonder, really. The expedition took place at a time when the political theories of the day still had to be propagated by the printed word. Nowadays censorship, like Apartheid, is a thing of the past. The Golden Harvest and Fri book project, launched under the name “Operation Namibia”, is one of the last great adventures in the history of the book.

So I had another go. New Zealand is a small country and the second voice to pick up the phone belonged to Anna. My book describes people handing round photos of her as a new born baby. She had saved her parents’ lives – they had left the Rainbow Warrior to check up on her just before the French secret services blew it up. She was also the reason they had left the Golden Harvest, having met for the first time on the trip. That, too, just in time

The shock came later. After years of preparation, the manuscript was nearly ready. Then came the news that Kris was dead. He could have written the book himself – he had been the group’s press and public relations officer. He had even send me a fax telling me how he still dreamed of writing a Golden Harvest book, when he no longer had more important things to do, like saving the rainforest. A memorial gathering was held. They all came back for that.

The meeting in London was pleasant enough. There was pasta and South African wine. We played his favourite songs, passed around photos and watched videos of some of his rainforest escapades. It was like a reunion of kamikaze ground support personnel. Someone said Morishta, the Japanese monk, had been spotted again in America, so he is probably still alive. On the other hand, no-one knew what had become of Momo.

They gave me the Golden Harvest log to copy. Barry, by the way, is convinced that Kris was murdered. He is also planning a trip to South Africa. He wants to do some investigative work to find out if the secret services were involved. Because if you really think about it, “Operation Namibia” couldn’t fail. And now the operation has turned into a book, just like a book should be – an adventure story with real protagonists.